Every modern application has a requirement for encrypting certain amounts of data. The traditional approach has been either relying on some sort of transparent encryption (using something like encryption at rest capabilities in the storage, or column/field level encryption in database systems). While this clearly minimizes the requirement for encryption within the application, it doesn’t secure the data from attacks like a SQL Injection, or someone just dumping data since their account had excessive privileges, or though exposure of backups.

In comes the requirement of doing encryption at the application level, with of course the expected complexity of doing a right implementation at the code level (choosing the right cyphers, encryption keys, securing the objects), and securing and maintaining the actual encryption keys, which more often than not, end in version control, or in some kind of object store subject to the usual issues.

Traditionally, there has been different approaches to secure encryption keys: An HSM could be used, with considerable performance penalty. An external encryption system, like Amazon’s KMS, or Azure Key Vault, or Google KMS’s, where the third party holds your encryption key. Ultimately, HashiCorp’s Vault offers it’s own Transit backend, which allows (depending on policy) to offload encryption/decryption/hmac workflows, as well as signing and verification, abstracting the complexity around maintaining encryption keys, and allowing users and organizations to retain control over them inside Vault’s cryptographic barrier. As a brief summary of Vault’s capabilities, when it comes to encryption as a service, we can just refer to Vault’s documentation.

The primary use case for transit is to encrypt data from applications while still storing that encrypted data in some primary data store. This relieves the burden of proper encryption/decryption from application developers and pushes the burden onto the operators of Vault. Operators of Vault generally include the security team at an organization, which means they can ensure that data is encrypted/decrypted properly. Additionally, since encrypt/decrypt operations must enter the audit log, any decryption event is recorded.

The objective of this article, however, is not to explain the capabilities of Vault, but rather to do an analysis of what’s the overhead of using Vault to encrypt a single field in the application.

For that purpose, a MySQL data source is used, using the traditional world database (with about 4000 rows), and the test being run will effectively launch a single thread per entry, that will encrypt a field of such entry, and then persist it to Amazon S3.

This test was run on an m4.large instance, in Amazon, running a Vault Server, with a Consul backend, a MySQL server, and the script taking the metrics, all on the same system. It is inspired on a traditional Big Data use case, where information needs to be persisted to some sort of object store for later processing. The commented Python function being executed in each thread is as follows:

def makeJson(vault, s3, s3_bucket, ID, Name, CountryCode, District, Population):

# Take the starting time for the whole function

tot_time = time.time()

# Take the starting time for encryption

enc_time = time.time()

# Base64 a single Value

Nameb64 = base64.b64encode(Name.encode('utf-8'))

# Encrypt it through Vault

NameEnc = vault.write('transit/encrypt/world-transit', plaintext=bytes(Nameb64), context=base64.b64encode('world-transit'))

# Calculate how long it took to encrypt

eetime = time.time() - enc_time

# Create the object to persist and convert it to JSON

Cityobj = { "ID": ID, "Name": NameEnc['data']['ciphertext'], "CountryCode": CountryCode, "District": District, "Population": Population }

City = json.dumps(Cityobj)

filename = "%s.json" % ID

# Take the starting time for persisting it into S3, for comparison

store_time = time.time()

# Persist the object

s3.put_object(Body=City, Bucket=s3_bucket, Key=filename)

# Calculate how long it took to store it

sstime = time.time() - store_time

# Calculate how long it took to run the whole function

tttime = time.time() - tot_time

print("%i,%s,%s,%s\n" % (int(ID), str(sstime), str(eetime), str(tttime)))

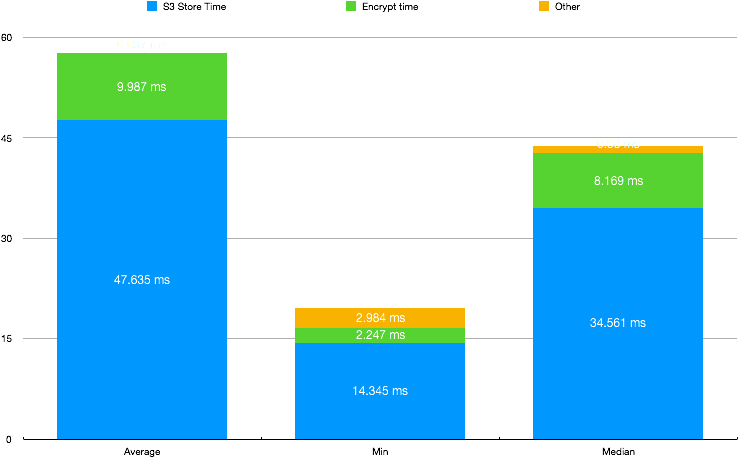

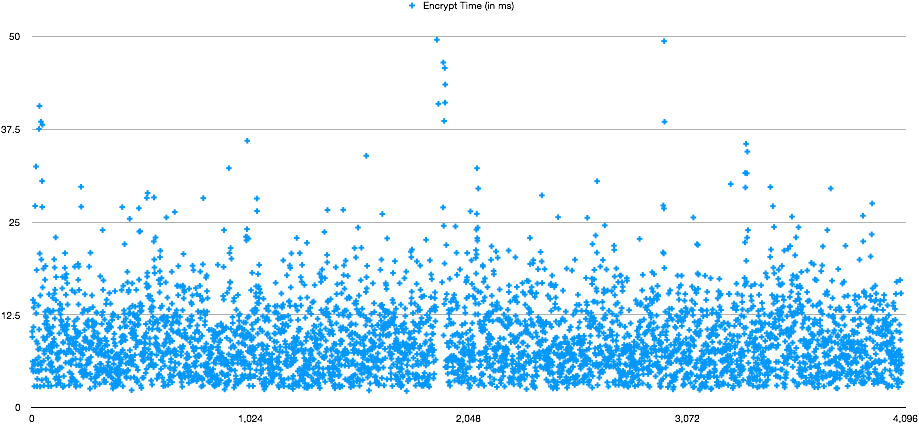

This would render a single line of a CSV, per thread, that later was aggregated in order to analyze the data. The average, minimum and median values are as follows:

As for concurrency, this is running 4 thousand threads that are being instantiated on a for loop. According to this limited dataset (about 4000 entries) we’re looking at a 5% ~ 10% overhead, in regards to execution time.

It’s worth noting that during the tests Vault barely break a sweat, Top reported it was using 15% CPU (against 140% that Python was using). This was purposely done in a limited scale, as it wasn’t our intention to test how far could Vault go. Vault Enterprise supports Performance replication that would allow it to scale to fit the needs of even the most demanding applications. As for the development effort, the only complexity added would be adding two statements to encrypt/decrypt the data as the Python example shows. It’s worth noting that Vault supports convergent encryption, causing same encrypted values to return the same string, in case someone would require to look for indexes in WHERE clauses.

Using this pattern, along with the well known secret management features in Vault, would help mitigate against the Top 10 database attacks as documented by the British Chartered Institute for IT:

-

Excessive privileges: Using transit, in combination of Vault’s Database Secret Backend, an organization can ensure that each user or application get’s the right level of access to the data, which in its own can be encrypted, requiring further level of privilege to decode it.

-

Privilege abuse: Using transit, the data obtained even with the right privileges is encrypted, and potentially requiring the right “context” to decrypt it, even if the user has access to.

-

Unauthorized privilege elevation: Much like in the cases above, Vault can determine what is the right access a user gets to a database, effectively terminating the “Gold credentials” pattern and encrypting the underlying data from operator access.

-

Platform vulnerabilities: Even if the platform is vulnerable, the data would be secure.

-

SQL injection: As data is not transparently encrypted, a vulnerable application would mostly dump obfuscated data, that can be re-wrapped upon detection of a vulnerability to an updated encryption key.

-

Weak audit: Vault audits encryption and decryption operations, effectively creating an audit trail which would allow to pinpoint exactly who has access to the data.

-

Denial of service: Through Sentinel, our policy as code engine, Vault can evaluate traffic patterns through rules and deny access accordingly.

-

Database protocol vulnerabilities: As before, even if the data is dumped, it wouldn’t be transparently decrypted.

-

Weak authentication: Using Vault’s Database secret backend, would generate short lived credentials which can be revoked centrally, and have the right level of complexity.

-

Exposure of backup data: Backups would be automatically encrypted, just like the underlying data.

About the author: Nicolas Corrarello is the Regional Director for Solutions Engineering @ HashiCorp based out of London.